LINUX-FU: RUNNING COMMANDS

One of the things that makes Linux and Unix-like systems both powerful and frustrating is that there are many ways to accomplish any particular goal. Take something simple like running a bunch of commands in sequence as an example. The obvious way is to write a shell script which offers a tremendous amount of flexibility. But what if you just want some set of commands to run? It sounds simple, but there are a lot of ways to issue a sequence of commands ranging from just typing them in, to scheduling them, to monitoring them the way a mainframe computer might monitor batch jobs.

Let’s jump in and take a look at a few ways you can execute sequences from bash (and many other Linux shells). This is cover the

cron and at commands along with a batch processing system called task spooler. Like most things in Linux, this isn’t even close to a complete list, but it should give you some ideas on ways to control sequences of execution.FROM THE SHELL

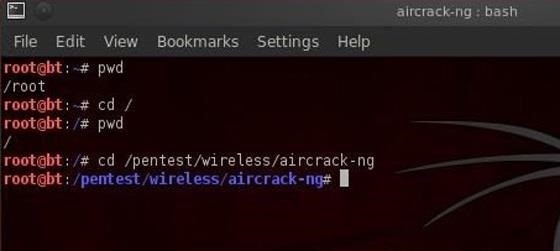

The easiest but perhaps least satisfying way to run a bunch of commands is right from the bash shell. Just put semicolons between the commands:

date ; df ; free

This works for many shells that look more or less like bash. For a simple set of commands like that, this is fine. Each one runs in sequence. However, what if you had this:

You want to erase all the files in foo (but not subdirectories; you’d need -r for that). But what if the

cd fails? Then you’ll erase all the files in whatever directory you happen to be in. That’s a bad idea and violates the law of least astonishment.

The solution is to use the && operator. Just like in C, this is an

AND operator. Nearly all Linux programs return a 0 error status for true and anything else is false. That allows programmers to return an error code for failure and it becomes a false. So consider this:cd /foo && ls # not rm so we don't do anything bad by mistake

If /foo exists, the

cd command will return 0 which is true. That means the result of the AND could be true and therefore execution continues with the ls. However, if the cd fails, the result will be false. If any input to an ANDfunction is false, the other values don’t matter. Therefore, as soon as anything returns false, the whole thing stops. So if there is no /foo, the ls command won’t execute at all.

You can use more than one set of these operators like:

There’s also an

OR operator (||) that quits as soon as anything returns true. For example:grep "alw" /etc/passwd || echo No such user

Try your user ID instead of alw and then try one that isn’t good (surely you don’t have a user named alw). If the

Try your user ID instead of alw and then try one that isn’t good (surely you don’t have a user named alw). If the grep succeeds, the echo doesn’t happen. You can even mix the operators if you like. If you have a lot of commands that take a long time to run, this may not be the best answer. In that case, look at Spooling, below.

You probably know that you can push a running command into the background by pressing Control+Z. From there you can manipulate it with

fg (move to foreground), bg (run in background), and kill commands. All of those techniques work with chained commands, too.TIMING

Sometimes you want to run commands at a predetermined time interval or at a particular time. The classic way to manage timed execution is

cron. Many distributions provide predefined directories that run things every hour, every minute, etc. However, the best way is to simply edit your crontab. Usually, you’ll create a script and then use that script in the crontab, although that’s not always necessary.

The crontab is a file that you must edit with the

crontab command (execute crontab -e). Each line that isn’t a comment specifies a program to run. The first part of the line tells you when to run and the last part tells you what to run. For example, here’s an entry to run the duckdns update program:*/5 * * * * ~/duckdns/duck.sh >/dev/null 2>&1

The fields specify the minutes, hour, day of the month, month and day of the week. The

*/5 means every 5 minutes and the other * mean any. There’s a lot of special syntax you can use, but if you want something easy, try this crontab editor online (see figure).

One problem with cron is that it assumes your computer is up and running 24/7. If you set a job to run overnight and the computer is off overnight, the job won’t run. Anacron is an attempt to fix that. Although it works like chron (with limitations), it will “catch up” if the computer was off when things were supposed to run.

Sometimes, you just want to run things once at a certain time. You can do that with the at command:

at now + 10 minutes

You will wind up at a simple prompt where you can issue commands. Those commands will run in 10 minutes. You can specify absolute times, too, of course. You can also refer to 4PM as “teatime” (seriously). The

atq command will show you commands pending execution and the atrm command will kill pending commands, if you change your mind. If you use the batch form of the command, the system will execute your commands when the system has some idle time.

If you read the man page for at, you’ll see that by default it uses the “a” queue for normal jobs and “b” for batch jobs. However, you can assign queues a-z and A-Z, with each queue having a lower priority (technically, a higher nice value).

One important note: On most systems, all these queued up processes will run on the system default shell (like /bin/sh) and not necessarily bash. You may want to explicitly launch bash or test your commands under the default shell to make sure they work. If you simply launch a script that names bash as the interpreter (

#!/usr/bin/bash, for example), then you won’t notice this.SPOOLING

Although the

at command has the batch alias, it isn’t a complete batch system. However, there are several batch systems for Linux with different attributes. One interesting choice is Task Spooler (the task-spooler in the Ubuntu repositories). On some systems, the command is ts, but since that conflicts on Debian, you’ll use tsp, instead.

The idea is to use

tsp followed by a command line. The return value is a task number and you can use that task number to build dependencies between tasks. This is similar in function to at, but with a lot more power. Consider this transcript:alw@enterprise:~$ tsp wget http://www.hackaday.com

0

alw@enterprise:~$ tsp

ID State Output E-Level Times(r/u/s) Command [run=0/1]

0 finished /tmp/ts-out.TpAPIV 0 0.22/0.00/0.00 wget http://www.hackaday.com

alw@enterprise:~$ tsp -i 0

Exit status: died with exit code 0

Command: wget http://www.hackaday.com

Slots required: 1

Enqueue time: Fri Jun 9 21:07:53 2017

Start time: Fri Jun 9 21:07:53 2017

End time: Fri Jun 9 21:07:53 2017

Time run: 0.223674s

alw@enterprise:~$ tsp -c 0

--2017-06-09 21:07:53-- http://www.hackaday.com/

Resolving www.hackaday.com (www.hackaday.com)... 192.0.79.32, 192.0.79.33

Connecting to www.hackaday.com (www.hackaday.com)|192.0.79.32|:80... connected.

HTTP request sent, awaiting response... 301 Moved Permanently

Location: http://hackaday.com/ [following]

--2017-06-09 21:07:53-- http://hackaday.com/

Resolving hackaday.com (hackaday.com)... 192.0.79.33, 192.0.79.32

Reusing existing connection to www.hackaday.com:80.

HTTP request sent, awaiting response... 200 OK

Length: unspecified [text/html]

Saving to: ‘index.html’

0K .......... .......... .......... .......... .......... 1.12M

50K .......... .......... .......... ... 6.17M=0.05s

2017-06-09 21:07:53 (1.68 MB/s) - ‘index.html’ saved [85720]

The first command started the

wget program as a task (task 0, in fact). Running tsp shows all the jobs in the queue (in this case, only one and it is done). The -i option shows info about a specified tasks and -c dumps the output. Think of -c as a cat option and -t as a tail -f option. You can also get output mailed with the -m option.

Typically, the task spooler runs one task at a time, but you can increase that limit using the -S option. You can make a task wait for the previous task with the -d option. You can also use -w to make a task wait on another arbitrary task.

If you look at the man page, you’ll see there are plenty of other options. Just remember that on your system the ts program could be tsp (or vice versa). You can also find examples on the program’s home page. Check out the video below for some common uses for task spooler.

Like most things in Linux, you can combine a lot of these techniques. For example, it would be possible to have cron kick off a spooled task. That task could use scripts that employ the

&& and || operator to control how things work internally. Overkill? Maybe. Like I said earlier, you could just bite the bullet and write a script. However, there’s a lot of functionality already available if you choose to use any or all of it.